Chromium steel, commonly referred to as stainless steel, is thought to be a recent industrial innovation, but new evidence indicates that ancient Persians stumbled upon an early version of this alloy about 1,000 years ago, in a surprise to archaeologists.

The ancient Persians had been making alloys made of chromium steel since the 11th century AD, according to Al Jadid Research Published today in the Journal of Archeology. This was probably steel They are used in the production of swords, daggers, shields and other things, but these minerals also contain phosphorous, which makes them brittle.

“This special crucible steel made in Chahak contains about 1% to 2% chromium and 2% phosphorous,” Rachel Alibor, lead author of the new study and archaeologist at University College London, said In a letter.

Archaeologists And historians, up until this point, were fairly certain that chrome steel (not to be confused with chrome – this another thingIt was a recent invention. Indeed, stainless steel as we know it today was developed in the twentieth century And It contains much more chrome than the steel produced by the ancient Persians. Alipur said that ancient Persian chrome steel “was not stainless steel.”

However, the new paper “provides the first evidence of the consistent and deliberate addition of the chromium metal, probably chromite, to the crucible steel charge – leading to the intentional production of low chromium steels,” the researchers write in a study.

G / O Media may receive a commission

A translation of medieval Persian manuscripts led the research team to Chahak, an archaeological site in southern Iran. Chahak used to be an important center for steel production, and it is the only archaeological site in Iran that has evidence of crucible making, where iron is added to long tube crucibles, along with minerals and other organic materials, which are then closed and heated in the furs.OnM. After cooling, the ingot is removed by breaking the crucible. This technique was of vital importance among many cultures, including the Vikings.

“ Crucible steel is generally very highAlibor said. “It does not contain impurities and is very ideal for producing weapons, armor and other tools.”

One of the main manuscripts used in the study was written by the Persian polymath Abu Rayhan Biruni, and it dates back to the tenth or eleventh century AD. The manuscript, entitled “Masses in the Knowledge of Gems” (translated as “Brief to Identify Gems”), provided instructions for crucible steel forging, but included an obscure compound called rusakhtaj (Meaning “burnt out”), which the researchers interpreted And then I determined On it is a sand of chromite.

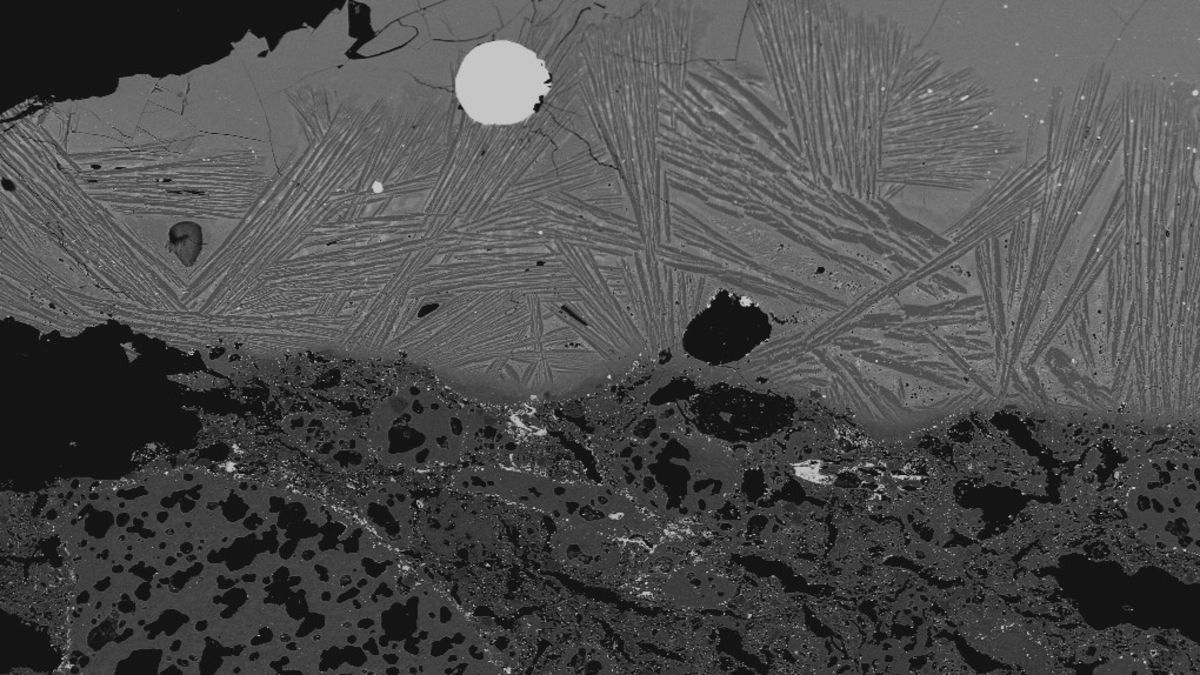

Excavations at Chuck resulted in the discovery of coal remains In old crucible slag (waste material left after the metal is separated). Radiocarbon dating of this coal yielded a time scale between the 10th and 12th centuries AD. A scanning electron microscope was used to analyze slag samples, revealing traces of chromite ore. Finally, the analysis of steel particles present in the slag indicates that Chahak crucible steel contains between 1% to 2% chromium by weight.

“The crucible steel made of chromium made in JHIC is the only one of its kind known to contain chromium, an element known to us for its importance in the production of modern steels, such as stainless steel and tools,” Alipore explained. “Chahak crucible steel would have been similar in terms of its properties to modern tool steels,” and “the chromium content would increase the strength and toughness, properties needed for tool making.”

She said that a wealth of steel objects with a Persian crucible can be found in museums around the world, and we already know that steel crucible was used to make arms with flanges and armor. Prestigious things, And other tools. Chahak is also referred to in historical manuscripts as a place where crucible feathers and swords were made, but accounts “also state that the blades were sold at a very high price, but were fragile, so they lost their value.”

Phosphorous, which was also detected during analysis, was added to reduce the melting point of the metal But also to reduce some hardness, which later made the metal brittle.

Regardless, the find points to a specific Persian tradition of steelmaking, which is very important in and of itself. As far as the authors know, the specific chromium content in Chahak steel can be used to distinguish it from other artifacts.

“Evidence for previous crucible steel, which scholars have studied, belongs to crucible steel production centers in India, Sri Lanka, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan,” Alibor said. “None of these exhibit any trace of chromium. Therefore, chromium has not been identified as an essential ingredient in the production of Chahak crucible steel in any other known steel industry to date.” She added, “This is very important, Where we can now look for this element in crucible steel objects and trace it back to the center or method of its production. “

To this end, the researchers hope to work with museum experts to share their findings To help with dating and identification Objects bear this unique chrome steel signature.

Communicator. Reader. Hipster-friendly introvert. General zombie specialist. Tv trailblazer